ADHD Awareness Week: Oct. 16-22

Posted: October 16, 2011 Filed under: education, just because, psychology | Tags: ADHD, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, brain imaging, language development, literacy, narrative, private speech 31 CommentsThis week is ADHD Awareness Week. I’ve been thinking about what I’ve learned about this developmental disorder over the past decade or so; and I thought I’d share some of it with you.

I used to be somewhat skeptical about the existence of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). After all, this supposed disorder didn’t exist when I was a kid, as far as I knew. (It turns out the behavior patterns associated with ADHD were observed as early as the 1790s). It seemed to me a bad idea to give children speed, which is basically what the stimulant drugs used to treat ADHD are.

When I went back to college to study psychology, I became friends with another student who had the diagnosis. Interacting with this young man and observing his behavior convinced me that ADHD really does exist.

My friend (I’ll call him “Bill”) had difficulty paying attention in class and sometimes he would stare out the window for long periods of time. He had trouble concentrating on writing assignments, because he was easily distracted. Paradoxically, Bill could focus his attention for long periods of time on something he found very interesting, like using the computer, playing music, or running. Those are common symptoms of ADHD.

People with ADHD tend to be impulsive–they may do or say things without thinking about the consequences, and this can lead to problems with other people.

I saw Bill get into trouble in his personal relationships again and again. He would make appointments to spend time with someone, forgetting that he had already made an appointment with another person–sometimes even two or three other people–for the same day and time. He often had to call people and cancel plans because of this. Most of the time, friends were understanding, but Bill ran into trouble when he made these mistakes in interactions with professors and other people he wanted to impress.

Although I liked Bill very much, I admit that I tired of hearing about his constant scheduling mixups, and about people who were angry with him about them. He wasn’t always easy to be friends with.

Something else I noticed in my interactions with my friend Bill was that he often used language in unusual and interesting ways. He sometimes had difficulty finding the right word and would make up words or describe emotions and behavior in unexpected ways. It’s possible that Bill had some kind language disorder in addition to ADHD, but he told me that he could often recognize fellow sufferers by the way they used words. I came to believe that Bill thought about things from a different perspective than most people, and I found that aspect of his ADHD somewhat charming.

As an undergraduate, I became fascinated with children’s language development; and I went on to specialize in that field in graduate school. One of the papers I wrote in order to qualify as a Ph.D. candidate was about ADHD and two aspects of language development: private speech and narrative (storytelling).

Private speech is self talk that young children use to support their play and other activities. They speak out loud to themselves, describing what they are doing or working out problems as they go along. Here’s an example:

A number of researchers have found that children with ADHD use more private speech and use it for about 3 years longer than typically developing children, who have generally stopped talking out loud to themselves by age 7 or 8. Children with ADHD may continue to do so until age 11 or so. The assumption is that children with ADHD use private speech more than other children because it helps them stay focused on tasks.

My main focus in graduate school was on children’s narrative development–basically the way children develop the skills used in telling stories. Narrative skills are used in forming autobiographical memories as well as in structuring reality and understanding the world around us. They are also an important facet of early literacy and an important predictor of how well children will perform academically. Children with ADHD tend to tell stories that are more poorly organized and less cohesive than those told by typically developing children.

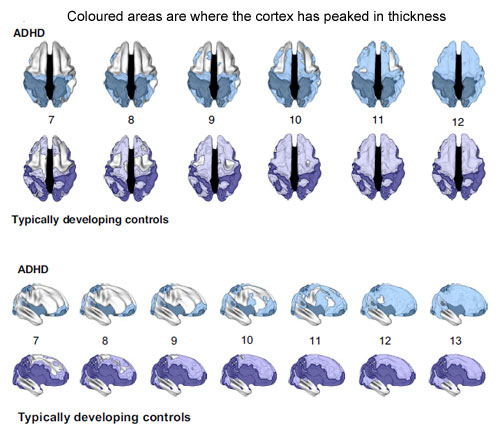

So there are a couple of concrete examples of differences in language abilities between children with ADHD and typically developing children. In recent years there have also been brain imaging students that demonstrate that the brains of children with ADHD develop more slowly in some ways than the brains of typically developing children. Here’s one example:

Philip Shaw, Judith Rapaport and others from the National Institute of Mental Health have found new evidence [that]….When some parts of the brain stick to their normal timetable for development, while others lag behind, ADHD is the result….they used magnetic resonance imaging to measure the brains of 447 children of different ages, often at more than one point in time.

At over 40,000 parts of the brain, they noted the thickness of the child’s cerebral cortex, the brain’s outer layer, where its most complex functions like memory, language and consciousness are thought to lie….

In both groups of children, parts of the cortex peaked in terms of thickness in the same order, with waves of maturity spreading from the edges to the centre….[but] the brains of ADHD children matured about three years later than those of their peers. Half of their cortex has reached their maximum thickness at age 10 and a half, while those of children without ADHD did so at age 7 and a half[.]

Isn’t it interesting that children with ADHD tend to lag behind in brain development by about three years–about the same length of time they continue to using private speech after typically developing children have stopped?

Here’s another blog entry on a different study of brain development in children with ADHD. This study found that children with ADHD had smaller caudate nuclei than typically developing children. This was a small study of 26 5-year-olds.

The basal ganglia (or basal nuclei) are the parts of the brain involved with voluntary motion and some forms procedural learning (development of a motor skill through practice, such as playing a musical instrument). The caudate nucleus specifically functions in learning and memory; it tells the cortex (the area of our brain where higher reasoning occurs) to do something based on current conditions. Importantly, the caudate nucleus controls motor skills partly through inhibition of particular behaviors, and disinhibition of others; an overactive caudate nucleus may be implicated in obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Smaller caudate nuclei had been documented before in older children with ADHD, but not before in children so young. The authors point out that previous studies have not been able to sort out what comes first: changes in brain structure or the behavior, which is part of the motivation of looking at younger children.

Just in time for ADHD Awareness Week, new guidelines have been released for the treatment of ADHD in children as young as 4. I must admit I find that a bit troubling. I hate to see kids get labeled as having a psychological disorder before they even start kindergarten. From the Wall Street Journal:

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder can be diagnosed in children as young as age four, according to new treatment guidelines by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The guidelines, released Sunday at the academy’s annual meeting in Boston, provide instructions for pediatricians on diagnosing and managing ADHD in children four to 18. They say behavioral management techniques should be the first treatment approach for preschool-age children.

But they also suggest doctors consider prescribing methylphenidate, commonly known by the brand name Ritalin, in preschool-age children with moderate to severe symptoms when behavior interventions don’t provide significant improvement. It’s a potentially controversial recommendation, because these medicines aren’t approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in that age group.

I’m not an expert on ADHD, but I am recovering addict, and I worry about children so young being given powerful mind-altering drugs. My friend “Bill” had been prescribed Ritalin as a child, and he felt that using the drug had resulted in his abusing cocaine and alcohol as a young adult.

Generally speaking, I’d like to see doctors, teachers, and parents use behavioral solutions for ADHD symptoms, rather than drugs. At the same time, I know that psychoactive drugs have been extremely helpful to me in dealing with severe depression. There are times when drugs are a good solution, but only in concert with therapy and self-awareness.

Again, I haven’t had a great deal of practical experience with ADHD. I’d be interested in hearing from anyone here who has. All-in-all, I think it’s a good thing that developmental disorders are recognized now more than when I was a kid. I can only assume that some kids fell through the cracks back then, while now kids with these problems get attention and treatment–however flawed it may be.

Recent Comments