Dollar Dazed

Posted: May 9, 2009 Filed under: Global Financial Crisis, U.S. Economy | Tags: Dollars, Eurodollars, IMF, international currency, SDRs, Special Drawing Rights 2 CommentsOne of the debates coming out of the global financial crisis is the potential for the U.S. Dollar to loose its supremacy as  the safe-haven and international reserve currency of choice. The dollar has not experienced this kind of problem since the 1970s when U.S. inflation threatened the Bretton Woods agreement. The threat to the dollar’s supremacy is based on different issues this time around. The first issue is the pervasive and increasingly huge U.S. trade deficit which has contributed to huge dollar holdings in oil rich countries and China. The second issue is the widespread acceptance and credibility of the Eurodollar.

the safe-haven and international reserve currency of choice. The dollar has not experienced this kind of problem since the 1970s when U.S. inflation threatened the Bretton Woods agreement. The threat to the dollar’s supremacy is based on different issues this time around. The first issue is the pervasive and increasingly huge U.S. trade deficit which has contributed to huge dollar holdings in oil rich countries and China. The second issue is the widespread acceptance and credibility of the Eurodollar.

Prior to the GS 2- meeting, China called for replacement of the U.S. Dollar by Special Drawing Rights (SDR) as the international reserve currency. This would certainly diminish U.S. economic influence around the world. What is an SDR and what is the chance it will supplant the Dollar as the currency of choice in the global economy? The best place to learn about Special Drawing Rights is to go straight to the IMF website.

The SDR is an international reserve asset, created by the IMF in 1969 to supplement the existing official reserves of member countries. SDRs are allocated to member countries in proportion to their IMF quotas. The SDR also serves as the unit of account of the IMF and some other international organizations. Its value is based on a basket of key international currencies.

As you can see, SDRs have been around for some time. They were created during the inflationary period of US history to support the Bretton Woods Agreement. This agreement established a fixed exchange rate regime to help build the global economy as it was experiencing World War 2. Bretton Woods is a small town in New Hampshire and served as the meeting place for the representatives of the 44 Allied Nations. This agreement was the basis of international currency evaluation until it’s official demise in 1976 in Jamaica. The system had collapsed prior to that date so the Jamaican agreement was really just an ex poste meeting to officiate the end.

Since then, most of the world’s currencies are traded on markets and the market determines their exchange rates. This is called a flexible exchange rate regime. Not all countries have flexible exchange rates. Some countries (because of weak governments or problems with inflation) peg their currencies to a stronger currency in their geographic area. Other countries adopt the currency of their economically stronger neighbors. Some form currency unions where they share a common currency. The biggest of these unions is the Eurozone which remains a coalition of politically independent countries that rely on the Eurodollar for trade. Both the Wikki site I referenced above as well as the International Monetary Fund site have some really interesting historical backgrounds and are worth the read. I’ve read through the Wikki reference and can guarantee that information on it is correct so that I do not have to send you to a textbook or someplace more complex. (International Trade, Finance, and Macroeconomics are my primary research areas now. I’ve somewhat branched out from my first masters area which was just basically the Financial economy of the U.S. and it’s the subject of my dissertation.)

The SDR is the unit of account for the IMF and other international development funds. It’s not really a currency or a money as we tend to think of monies today. This is because it is not a claim on the IMF in the way that a dollar bill is a claim on the Federal Reserve Bank and essentially the U.S. Treasury. It is a potential claim on the set of currencies that it represents. These currencies are basically those of the IMF members and they are placed in what is known as a basket. The basket is a weighted average of all the currencies of the members. This is how SDRs are ‘created’ (also from the IMF link.) Today the basket consists of the yen, the Eurodollar, the U.S. dollar, and the U.K. pound sterling.

The U.S. dollar-value of the SDR is posted daily on the IMF’s website. It is calculated as the sum of specific amounts of the four currencies valued in U.S. dollars, on the basis of exchange rates quoted at noon each day in the London market.

The basket composition is reviewed every five years to ensure that it reflects the relative importance of currencies in the world’s trading and financial systems. In the most recent review in November 2005, the weights of the currencies in the SDR basket were revised based on the value of the exports of goods and services and the amount of reserves denominated in the respective currencies which were held by other members of the IMF. These changes became effective on January 1, 2006. The next review by the Executive Board will take place in late 2010.

Since the SDR is not really a currency, it does not perform the most important function that a money serves. It is not a universally accepted means of exchange. Because it does not serve this purpose, it is unlikely to replace either the Dollar or the Eurodollar as any kind of currency.

There are other issues with SDRs and that makes the question of them being used as some kind of international currency that would eventually supplant the U.S. dollar more rhetorical than practical. Here is Federal Reserve Senior Economic Adviser Owen Humpage from Fed Cleveland on VOX.

There are other issues with SDRs and that makes the question of them being used as some kind of international currency that would eventually supplant the U.S. dollar more rhetorical than practical. Here is Federal Reserve Senior Economic Adviser Owen Humpage from Fed Cleveland on VOX.

The world reaps substantial economies from using dollars.

- Many foreign-exchange transactions, even ones not directly involving US residents, are denominated and undertaken in dollars.

International trade in fairly standardised commodities and in products that sell in highly competitive markets is typically conducted in US dollars. Invoicing in a single currency helps producers keep their prices in line with their competitors and simplifies price comparisons across the different producers. Naturally, these invoicing gains rise with the number of producers.

So what is China’s problem? Again from Humpage:

While China claims that credit-based national reserve currencies are inherently risky, facilitate global imbalances, and foster the spread of financial crises, the key concern may be a bit more parochial. The country holds a huge official portfolio of dollar-denominated assets that could incur valuation losses if recent US actions to limit financial turmoil and stimulate the economy generated inflation and dollar depreciation (not unrelated to the problems France faced with its 1920s “sterling trap”).

China may actually fear that the incredible loose monetary and fiscal policy implemented under the current Fed and Obama administration is likely to be inflationary. It fears a repeat of past crises like the Nixon shock. That may cause China to look at the Eurodollar more carefully. This is because Germany is a major playing in the European Central Bank, it lived through incredible hyperinflation during World War 2, and has already indicated that it doesn’t see the need for the kind of massive stimulus undertaken in the U.S. This means the Euro is unlikely to experience inflation. That may not be the case with either the U.S. Dollar or the U.K. pound sterling if either of those economies take off any time soon.

The real answer to China’s dilemma lies in its undervalued currency, it’s attempts to peg its currency to the dollar, and its attempts to control its interest rates while controlling its capital outflows. They’re trying to find a solution where none exists. Eventually, China will have to stop asking the world to grow their economy and turn to their own policies to improve their situation. The oil rich countries, the other dollar holders, are out buying undervalued commercial property in the U.S. right now. They don’t have the same complaints or issues.

So, will we see the fall of the dollar any time soon or the dread international currency? From what I can see, my answer is no. But if you’re that into conspiracy theories about the whole thing, I’m not likely to convince you anyway. I’ve never had much luck reasoning with a gold bug either so if you fall into those camps, you’re just going up to have to rant away without any support from me.

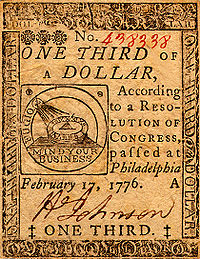

Oh, and while I’m disabusing people of things, please notice that I’ve included original copies of the first continental dollar (1776) and the first greenbacks (1867). Neither of them has “In God We Trust” on them. That was a much, much, much later edition (actually 1956). I rather like the motto on the continental dollars. It was “Mind Your Business”. I think that’s rather apt. Here’s a link to a 1923 $10 note and one to a 1923 $1 note. You’ll also notice its missing on those old greenbacks too. So, if you run into any one who says that motto has always been there, disabuse of them of the notion, quickly and you’ll have my eternal gratitude.

Didn’t a religious denomination (Mormons, perhaps) argue that ‘In God We Trust’ was a bad idea because money could be used for immoral purposes?

Setting that aside, is it possible that China could take long term treasuries and tell the US “we want our principal back now and we’ll give up any interest” in order to invest in another currency? Granted, it’s highly unlikely.

Well, they can’t do that, but they could dump their holdings on the secondary market or just not roll any over after they come to term. That would have a similar impact. However, the problem with dumping that many treasuries in the market would be to drive the price down so drastically that they would basically loose their shirts. I doubt they’d want to do that.